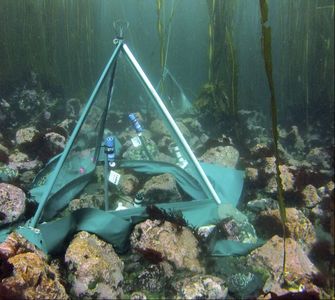

Benthic respiration chamber deployed in a transition zone Benthic respiration chamber deployed in a transition zone Sadie here with a brief expedition update and a look inside shipboard lab operations! The next island along our route was Agattu, but inclement weather forced us to head East sooner than expected. After a full travel day, we arrived at beautiful Kiska Island this morning. As usual, the Edwards Lab dive team deployed chambers in three different habitat types (kelp, transition, and urchin barren). A quick refresher on what our lab is doing up here in the Aleutians: we’re comparing ecosystem productivity between these three habitats and among different islands in an east-west gradient along the island chain. For this large-scale project, we use clear, flexible chambers to isolate 0.57m^2 patches of the seafloor for 24-hour periods, meanwhile collecting changing oxygen concentration, temperature, and light data within these chambers. The organisms in nearshore benthic habitats all use or produce oxygen during photosynthesis or respiration, so we use oxygen concentration to assess the activities of algae and animals within the chambers. These data help us estimate productivity from the community as a whole; however, we want to go deeper into the story! Algae and invertebrate animals from inside the chambers are collected and brought back to the ship and further analyzed to help us understand how individual members of the community are contributing to our large-scale production estimates.  Sadie conducting a photoincubation with green algae Sadie conducting a photoincubation with green algae That’s where Dr. Ju-Hyoung Kim and I come in. We’re using small-scale methods at the individual level to add details to the large-scale benthic chambers that give us community-level data. In the shipboard laboratory, we have set up small glass incubation chambers that hold one organism at a time. By controlling temperature and light, we can measure the change in oxygen concentration via photosynthesis (algae) and respiration (animals). Coupled with biomass data from the chambers, we hope tease apart how each species contributes to the larger productivity estimate within the benthic chambers that the dive team deploys in the field. These experiments in the field and in the laboratory allow our group of scientists to come together and work toward a common goal, which is to understand more about the valuable ecosystems of the Aleutian Islands!  Usually our common goal is research-related, but sometimes we get together and make algae art! Featured here in an herbarium pressing: Neoptilota asplenoides, Kallymeniopsis sp., Odonthalia setacea, Neinburgia prolifera, Callophyllis sp., and more. Catch you at the next island!

--SS

0 Comments

View of Adak Island from the plane. View of Adak Island from the plane. Tristin here! My flight out of California departs at 6:30am and my alarm set for 3:30am; but let’s be honest, I’ve been up since 2:00am. A year and a half ago I was working as a research technician, and was a prospective graduate student for Dr. Matthew Edwards at San Diego State University. He was looking for a group of students and scientific SCUBA divers to assist him on a three-week research cruise to the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, to look at the effects of the widespread loss of kelp forests on biodiversity, primary production, and nutrient cycling (for more info on our cruise and objectives, click here). Since then, my lab and I have spent the last year working long hours at SDSU’s marine lab (CMIL website) getting ready for this trip (fueled by coffee and burritos, obviously). And now, thirteen pairs of wool socks later, my bags are packed, my dive gear is trimmed, serviced, and ready for the trip. Packing for an expedition like this is as exhilarating as it is exhausting; we have to condense as much of our equipment (including drysuits and undergarments) as possible while adhering the airline’s strict 50lb bag limit. (Note: this did not work very well, as a lab we ended up checking 13 bags filled with science and diving gear. Restlessly lying in bed and reminiscing about my first year of graduate school wasn’t helping, so I powered two cups of coffee and jumped in the shower. By this time, it’s 3:00am and Colin (my ride and partner) has unfortunately been awakened by my ruckus and commotion. So, he sips on his first cup of coffee, I chug my third, and we’re off! From Santa Cruz, we make our way over to San Jose International Airport, say our goodbyes, and now it’s real; I’m headed to the most remote and western most part of the United States. The rest of my lab mates are flying from San Diego and Los Angeles, but we are meeting up in Portland. Snapchats through security irritate TSA, but my lab mates and I are adamant about documenting the moments leading up to our reunion. I get my boarding pass (San Jose to Portland to Anchorage to Adak), check in, at and 6:30am on the dot, we’re in the air. I land in Portland (which is by-far the best airport to have a 2-hr layover in), and immediately check in with mom and let her know I landed. Just as I pulled out a book to kill the time, I noticed a man carrying 40lbs of lead dive weight…It’s my labmate Scotty! In tow were (almost) the rest of the San Diego contingent, Dr. Matt Edwards, Dr. Ju-hyoung Kim (from Korea), Scotty Gabara, Genoa Sullaway, and Sadie Small, united at last! The only one we are missing at this point is Pike who is coming from Los Angeles, but he’s pretty travel savvy, so we aren’t too worried about him meeting up with us in Alaska. This stop is a quick one, we’re off to Anchorage!  Flying over Canada and Alaska was a dream. Thousands of miles of pristine lakes, valleys, and mountains are as far as I can see. The lakes are milky blue from snowmelt, and deep ravines run from mountain tops to the ocean. We land in Anchorage at around 2:00pm and are famished, so we forage for food with Brenda Konar’s Lab (University of Fairbanks Alaska, the other half of the scientific crew). Although we’ve only had conference calls and skype meetings with them over the last year, seeing them in person seemed so familiar. We finish eating and head to the terminal…then in the distance we witness a spectacular show of Pike running through the airport to make his flight. We greet him with hugs and leftovers, and then make our way to the terminal. We load up, and then minutes later we were in the air on our way to Adak Island, and our first moments in the remote Aleutian Archipelago. The three-hour and three-minute flight from Anchorage to Adak revealed a gradient of cloud coverage. The Edwards lab is additionally interested in abiotic factors (such as cloud cover) affecting the net primary production (photosynthesis) of a given area. Thoughts like this run through my head for the remainder of the flight, until we begin our descent and are below the clouds. Then, like an explosion of color, came the green hills, black lakes, white snow, and red, blue, yellow homes. At the height of WWII, the United States used Adak as a military base to house an estimated 60,000 troops. Now, there are about 300 people left on the island, leaving many of the homes, warehouses, and docks abandoned. Although there is a small population on the island, we are greeted at the airport by Alaska Fish and Wildlife biologists and two pick-up trucks. We load 13 scientists, their personal belongings, dive gear, and scientific equipment into the trucks and head over to the R/V Oceanus. We arrive at our new home, the R/V Oceanus, and rapidly unload gear from the trucks and begin the safety briefing. Safety is a big deal on a mission like ours considering we are traveling in one of the most remote places in the world. Captain Jeff and Marine Technician Brandon give us a run-down of the boat, and it’s emergency procedures, and then… We are off to Tanaga Island, AK…2,862 miles from where I began my trip this morning. Cheers, Tristin  Dr. Matthew Edwards diving in lush kelp forest in the Aleutians. (Photo Dr. Brenda Konar) Dr. Matthew Edwards diving in lush kelp forest in the Aleutians. (Photo Dr. Brenda Konar) Why: This is the big one, so it gets listed first. Why are we going to the Aleutians? The widespread loss of sea otters throughout the Aleutian Archipelago has resulted in a dramatic increase in sea urchin abundance and a corresponding loss of kelp forests. (THIS article is a great overview of ecological theory related to this topic and takes a deeper look into how sea otters ‘balance’ ecosystems, see the end of the article “Sea Otters and their Cascading Effects”). Our over-arching goal is to examine how the widespread loss of kelp forests effects primary production, biodiversity and nutrient cycling across a range of habitats in the Aleutian Archipelago. Who: Thirteen scientists will be participating in the shipboard research effort, including: Dr. Matthew Edwards and his lab from San Diego State University (Scott Gabara, Genoa Sullaway, Sadie Small, Tristin McHugh, and Pike Spector), Dr. Brenda Konar and her lab from University Alaska Fairbanks, (Ben Weitzman, Jacob Metzger, Sarah Traiger, and Alex Ravelo), and Dr. Ju-Hyoung Kim from Chonnam National University in South Korea. What: On the cruise, scientists will be doing an array of activities with the common goal of assessing how the wide-spread loss of kelp along the archipelago influences the net ecosystem production and benthic biodiversity.

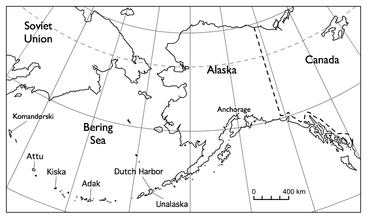

Where: The Aleutian Island chain spans 1,800 kilometers and has upwards of 300 islands of varying size (Figure 2). This summer we are visiting the Eastern Islands and will return to the archipelago in the summer of 2017 to survey the Western Islands. We are departing from Adak Island and will survey at total of 10 islands over the course of two years. In 2016, we will work at five of these islands (Adak, Atka, Chuginadak, Umnak, and Unalaska). The cruise will officially end in Dutch Harbor, and from there we will stay on the ship as it motors back to Seward where we will unload our gear and store it for next year’s expedition!

When: Starting now!! (June 16th) The cruise will last for 21 days and end in Seward, AK in early July. How: This trip is funded by the National Science Foundation, and logistically supported by Oregon State University’s R/V Oceanus captain and crew. Follow along for updates and pictures as the cruise progresses! |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed